Biography of Rabbi Arnold Josiah Ford

By

Rabbi Sholomo Ben Levy

Ford, Arnold Josiah (23 Apr. 1877-16

Sept. 1935), rabbi, black nationalist, and emigrationist, was born in

Bridgetown, Barbados, the son of Edward Ford and Elizabeth Augusta Braithwaite.

Ford asserted that his father’s ancestry could be traced to the Yoruba

tribe of Nigeria and his

mother’s to the Mendi tribe of Sierra Leone. According to his

family’s oral history, their heritage extended back to one of the

priestly families of the ancient Israelites, and in Barbados his family maintained

customs and traditions that identified them with Judaism (Kobre, 27). His

father was a policeman who also had a reputation as a “fiery

preacher’ at the Wesleyan Methodist Church where Arnold was baptized;

yet, it is not known if Edward’s teaching espoused traditional Methodist

beliefs or if it urged the embrace of Judaism that his son would later

advocate.

Ford’s parents intended for him to become a musician. They

provided him with private tutors who instructed him in several

instruments—particularly the harp, violin, and bass. As a young adult, he

studied music theory with Edmestone Barnes and in 1899 joined the musical corps

of the British Royal Navy, where he served on the HMS Alert. According to some reports, Ford was stationed on the island of Bermuda,

where he secured a position as a clerk at the Court of Federal Assize, and he

claimed that before coming to America

he was a minister of public works in the Republic of Liberia,

where many ex-slaves and early black nationalists settled.

When Ford arrived in Harlem around

1910, he gravitated to its musical centers rather than to political or

religious institutions—although within black culture, all three are often

interrelated. He was a member of the Clef Club Orchestra, under the direction

of James Reese Europe, which

first brought jazz to Carnegie Hall in 1912. Other black Jewish musicians, such

as Willie “the Lion” Smith, an innovator of stride piano, also

congregated at the Clef Club.

Shortly after the orchestra’s Carnegie Hall engagement, Ford

became the director of the New Amsterdam Musical Association. His interest in

mysticism, esoteric knowledge, and secret societies is evidenced by his

membership in the Scottish Rite Masons, where he served as Master of the Memmon

Lodge. It was during this period of activity in Harlem,

he married Olive Nurse, with whom he had two children before they divorced in

1924.

In 1917 Marcus Garvey

founded the New York

chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association [UNIA], and within a few

years it had become the largest mass movement in African American history.

Arnold Ford became the musical director of the UNIA choir, Samuel Valentine was

the president, and Nancy Paris its lead singer. These three became the core of

an active group of black Jews within the UNIA who studied Hebrew, religion, and

history, and held services at Liberty Hall, the headquarters of the UNIA. As a

paid officer, Rabbi Ford, as he was then called, was responsible for

orchestrating much of the pageantry of Garvey’s highly attractive

ceremonies. Ford and Benjamin E. Burrell composed a song called

“Ethiopia,” which speaks of a halcyon past before slavery and

stresses pride in African heritage—two themes that were becoming

immensely popular. Ford was thus prominently situated among those Muslim and

Christian clergy, including George

Alexander McGuire, Chaplain-General of the UNIA, who were each trying to

influence the religious direction of the organization.

Ford’s contributions to the UNIA, however, were not limited to

musical and religious matters. He and E.L. Gaines wrote the handbook of rules

and regulation for the paramilitary African Legion (which was modeled after the

Zionist Jewish Legion) and developed guidelines for the Black Cross Nurses. He

served on committees, spoke at rallies, and was elected one of the delegates

representing the 35,000 members of the New York

chapter at the First International Convention of Negro Peoples of the World,

held in 1920 at Madison

Square Garden.

There the governing body adopted the red, black, and green flag as its ensign,

and Ford’s song “Ethiopia”

became the “Universal Ethiopian Anthem,” which the UNIA

constitution required be sung at every gathering. During that same year, Ford

published the Universal Ethiopian Hymnal. Ford was a proponent of

replacing the term “Negro” with the term “Ethiopian,”

as a general reference to people of African descent. This allowed the biblical verse “Ethiopia

shall soon stretch out her hand to God,” (Psalm 68:3) to be interpreted

as applying to their efforts and it became a popular slogan of the

organization. At the 1922 convention, Ford opened the proceedings for the

session devoted to “The Politics and Future of the West Indian

Negro,” and he represented the advocates of Judaism on a five-person ad

hoc committee formed to investigate “the Future Religion of the

Negro.” Following Garvey’s arrest in 1923, the UNIA loss much of

its internal cohesion. Since Ford and his small band of followers were

motivated by principals that were independent of Garvey’s charismatic

appeal, they were repeatedly approached by government agents and asked to

testify against Garvey at trial, which they refused to do. However, in 1925, Ford

brought separate law suits against Garvey and the UNIA for failing to pay him

royalties from the sale of recordings and sheet music, and in 1926 the judge

ruled in Ford’s favor. No longer musical director, and despite his

personal and business differences with the organization, Rabbi Ford maintained

a connection with the UNIA and was invited to give the invocation at the annual

convention in 1926.

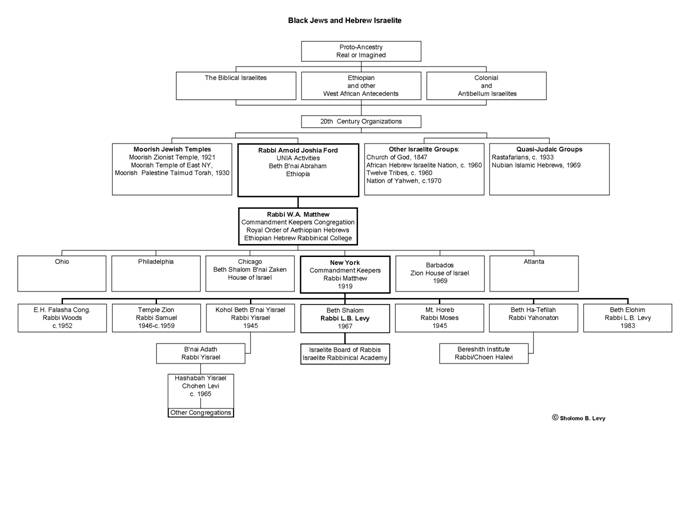

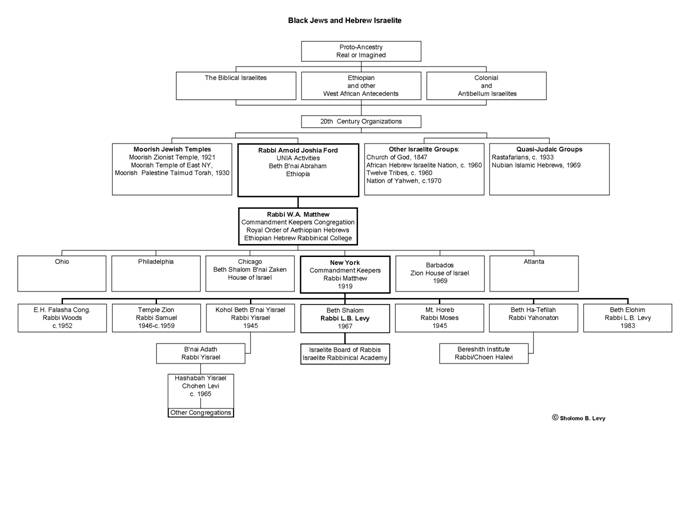

Several black religious leaders were experimenting with Judaism in

various degrees between the two world wars. Rabbi Ford formed intermittent

partnerships with some of these leaders. He and Valentine started a short lived

congregation called Beth B’nai Israel. Ford then worked with Mordecai

Herman and the Moorish Zionist Temple, until they had an altercation over theological

and financial issues. Finally, he established Beth B’nai Abraham in Harlem in 1924. A Jewish scholar who visited the

congregation described their services as “a mixture of Reform and

Orthodox Judaism, but when they practice the old customs they are seriously

orthodox” (Kobre, 25). Harlem chronicler James VanDerZee photographed the congregation with the Star

of David and bold Hebrew lettering identifying their presence on 135th

Street and showing Rabbi Ford standing in front of the synagogue with his arms

around his string bass, and with members of his choir at his side, the women

wearing the black dresses and long white head coverings that became their

distinctive habit and the men in white turbans.

In 1928, Rabbi Ford created a business adjunct to the congregation

called the B’nai Abraham Progressive Corporation. Reminiscent of many of

Garvey’s ventures, this corporation issued one hundred shares of stock

and purchased two buildings from which it operated a religious and vocational

school in one and leased apartments in the other. However, resources dwindled

as the Depression became more pronounced, and the corporation went bankrupt in

1930. Once again it seemed that Ford’s dream of building a black

community with cultural integrity, economic viability, and political virility

was dashed, but out of the ashes of this disappointment he mustered the resolve

to make a final attempt in Ethiopia.

The Ethiopian government had been encouraging black people with skills and

education to immigrate to Ethiopia

for almost a decade, and Ford knew that there were over 40,000 indigenous black

Jews already in Ethiopia

(who called themselves Beta Israel,

but who were commonly referred to as Falasha). The announced coronation of

Haile Selassie in 1930 as the first black ruler of an African nation in modern

times raised the hopes of black people all over the world and led Ford to

believe that the timing of his Ethiopian colony was providential.

Ford arrived in Ethiopia

with a small musical contingent in time to perform during the coronation

festivities. They then sustained themselves in Addis Abba by performing at

local hotels and relying on assistance from supporters in the United Sates who

were members of the Aurienoth Club, a civic group of black Jews and black

nationalists, and members of the Commandment Keepers Congregation, led by Rabbi W. A. Matthew, Ford’s most loyal

protégé. Mignon Innis arrived with a second delegation in 1931 to

work as Ford’s private secretary.

She soon became Ford’s wife, and they had two children in Ethiopia.

Mrs. Ford established a school for boys and girls that specialized in English

and music. Ford managed to secure eight hundred acres of land on which to begin

his colony and approximately one hundred individuals came to help him develop

it. Unbeknownst to Ford, the U.S. State Department monitored Ford’s

efforts with irrational alarm, dispatching reports with such headings as

“American Negroes in Ethiopia—Inspiration

Back of Their Coming Here—‘Rabbi’ Josiah A. Ford,” and

instituting discriminatory policies to curtail the travel of black citizens to Ethiopia.

Ford had no intention of leaving Ethiopia,

so he drew up a certificate of ordination (shmecha) for Rabbi Matthew

that was sanctioned by the Ethiopian government in the hope that this document

would give Matthew the necessary credentials to continue the work that Ford had

begun in the United States.

By 1935 the black Jewish experiment with Ethiopian Zionism was on the verge of

collapse. Those who did not leave because of the hard agricultural work, joined

the stampede of foreign nationals who sensed that war with Italy was imminent and defeat for Ethiopia

certain. Ford died in September, it was said, of exhaustion and heartbreak, a

few weeks before the Italian invasion. Ford had been the most important

catalyst for the spread of Judaism among African Americans. Through his

successors, communities of black Jews emerged and survived in several American

cities.

Further Reading

King, Kenneth J. “ Some Notes on Arnold

J. Ford and New World Black Attitudes to Ethiopia,” in Black

Apostles: Afro-American Clergy Confront the Twentieth Century, Randall

Burkett and Richard Newman, eds. (1978).

Kobre, Sidney. “Rabbi Ford,” The Reflex 4,

no. 1 (1929): 25-29.

Scott, William R. “Rabbi Arnold Ford’s Back-to-Ethiopia

Movement: A Study of Black Emigration, 1930-1935,” Pan-African Journal

8, no. 2 (1975):191-201.

* No part of these essays may be used without the

author’s permission.

Biography of Rabbi W.A. Matthew

By

Rabbi Sholomo Ben Levy

Chief Rabbi W.A. Matthew

Matthew,

Wentworth Arthur (23 June 1892-3 Dec. 1973), rabbi and educator, is believed to have been

born in St. Marys, St. Kitts, in the British West Indies, the son of Joseph

Matthew and Frances M. Cornelius. Matthew gave seemingly contradictory accounts

of his ancestry that put his place of birth in such places as Ethiopia, Ghana,

and Lagos, Nigeria. Some of those lingering

discrepancies were partially clarified when Matthew explained that his father,

a cobbler from Lagos, was the son of an

Ethiopian Jew, a cantor who sang their traditional liturgies near the ancient

Ethiopian capital of Gondar.

Matthew’s father then married a Christian woman in Lagos and they gave their son, Wentworth, the

Hebrew name Yoseh ben Moshe ben Yehuda, also given as Moshea Ben David. His

father died when he was a small boy and his mother took him to live in St.

Kitts, where she had relatives who had been slaves on the island (Ottley, 143).

In 1913 Matthew

immigrated to New York City, where he worked as a carpenter and engaged in

prize fighting, though he was just a scrappy five feet four inches tall. He

reportedly studied at Christian and Jewish schools, including the Hayden

Theological Seminary, the Rose of Sharon Theological Seminary (both now

defunct), Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, and even the University of

Berlin, but there is no independent evidence to corroborate his attendance at

these institutions. In 1916 Matthew married Florence Docher Liburd, a native of

Fountaine, Nevis, with whom he would have four

children. During the First World War, Matthew was one of many street exhorters

who used a ladder for a pulpit and Harlem’s

bustling sidewalks as temporary pews for interested pedestrians. By 1919 enough

people were drawn to his evolving theology of Judaism and black nationalism

that he was able to found “The Commandments Keepers Church of the living

God The pillar and ground of the truth And the faith of Jesus Christ.” He

attempted to appeal to a largely Christian audience by pointing out that

observance of the Old Testament commandments was the faith of Jesus; however,

it became apparent that visitors often missed this point and assumed that any

reference to Jesus implied a belief in Jesus. To avoid this confusion with

Christianity, Matthew ceased to use the title Bishop and removed all references

to Jesus from his signs and later from their papers of incorporation.

The transition from a

church-based organization holding Jewish beleifs to a functioning synagogue

that embraced most of the tenets of mainstream Orthodox Judaism was

accomplished by Matthew’s association with Rabbi Arnold Ford. Ford was a luminary in the Universal Negro

Improvement Association, a black nationalist organization led by Marcus Garvey. Rabbi Ford offered

Hebrew lessons and religious instruction to a number of laypeople and clergy in

the Harlem area. Ford worked with both

Matthew’s Commandments Keepers Congregation and the Moorish Zionist

Congregation led by Mordecai Herman in the 1920s before starting his own

congregation, Beth B’nai Abraham. In 1931, after Ford emigrated to Ethiopia he sent a letter to Matthew granting

him “full authority to represent Us in America” and furnishing him

with a Shmecah, a certificate of rabbinic ordination (Ford to

Matthew, 5 June 1931). Throughout the rest of his career, Matthew would claim

that he and his followers were Ethiopian Hebrews, because in their lexicon

Ethiopian was preferred over the term Negro, which they abhorred, and because

his authority derived from their chief rabbi in Ethiopia.

As an adjunct to his

congregation, Matthew created a Masonic lodge called The Royal Order of

Aethiopian Hebrews the Sons and Daughters of Culture. He became a U.S. citizen in 1924 and the following year

created the Ethiopian

Hebrew Rabbinical

College for the training

of other black rabbis. Women often served as officers and board members of the

congregation, though they could not become rabbis. In the lodge there were no

gender restrictions and woman took courses and even taught in the school.

Religion, history, and cultural anthropology, presented from a particular

Afrocentric perspective, were of immense interest to Matthew’s followers

and pervaded all of his teaching. The lodge functioned as a secret society

where the initiated explored a branch of Jewish mysticism called kabballah,

and the school sought to present a systematic understanding of the practice of

Judaism to those who initially adopted the religion solely as an ethnic

identity. While the black press accepted the validity of the black Jews in

their midst, the white Jewish press was divided; some reporters accepted them

as odd and considered their soulful expressions exotic, most challenged

Matthew’s identification with Judaism, and a few ridiculed “King

Solomon’s black children” and mocked Matthew’s efforts to

“teach young pickaninnies Hebrew” (Newsweek, 13 Sept. 1934).

Matthew traveled

frequently around the country, establishing tenuous ties with black

congregations interested in his doctrine. He insisted that the original Jews

were black and that white Jews were either the product of centuries of

intermarriage with Europeans or the descendents of Jacob’s brother Esau,

whom the bible describes as having a “red” countenance. Matthew

argued that the suffering of black people was in large measure God’s

punishment for having violated the commandments. When black people

“returned” to Judaism, he believed, their curse would be lifted and

the biblical prophecies of redemption would be fulfilled. Most of the black

Jewish congregations that sprung up in the post Depression era trace their

origin to Matthew or William Crowdy, a nineteenth century minister whose

followers also embraced some aspects of Judaism, but unlike Matthew’s

followers, never abandoned New Testament theology. When Matthew spoke of the

size of his following, he appeared to count many of these loose affiliations

and he also included those who expressed an interest in Judaism, not just those

who adhered to his strict doctrine of Sabbath worship, kosher food, bar

mitzvahs, circumcision, and observance of all Jewish holidays. The core of his

support came from a few small congregations in New York,

Chicago, Ohio,

and Philadelphia.

Many of his students established synagogues in other parts of New York City; often they were short-lived

and those that thrived tended to become revivals rather than true extensions of

Matthew’s organization.

During the second world

war, two of Matthews sons served in the military and the congregation watched

with horror as atrocities against Jews were reported. In 1942 Matthew published

the Minute Book, a short history of his life’s work, which he

described as the “most gigantic struggle of any people for a place under

the sun.” Matthew would later publish Malach (Messenger), a

community newsletter. Having supported the Zionist cause, the congregation

celebrated the creation of the state of Israel

in 1948, but by the 1950s their dreams of settling in Africa or Israel had been replaced by a more modest vision

of establishing a farming collective on Long Island.

The congregation purchased a few parcels of land in North Babylon in Suffolk County, New

York, and began building a community that was to

consist of a retirement home for the aged, residential dwellings, and small

commercial and agricultural industry. Opposition from local residents and

insufficient funding prevented the property from being developed into anything

more than a summer camp and weekend retreat for members, and the land was lost

in the 1960s.

When a new wave of black

nationalism swept the country during the civil rights movement, there were

brought periods of closer unity between blacks and Jews, but also painful

moments of tension in major cities. Matthew enjoyed a close relationship with Adam Clayton Powell Jr. in Harlem, with

Percy Sutton, who as Borough President of Manhattan

proclaimed a day in Matthew’s honor, and with congressman Charles Rangel,

who was a frequent guest at Commandment Keepers. Matthew also became affiliated

with Rabbi Irving Block, a young white idealist who had recently graduated from

Jewish Theological Seminary and started the Brotherhood Synagogue. Block

encouraged Matthew to seek closer ties with the white Jewish community and he

urged white Jewish institutions to accept black Jews. Matthew applied for

membership in the New York Board of Rabbis and in B’nai B’rith, but

was rejected. Publicly they said that Matthew was turned down because he was

not ordained by one of their seminaries; privately they questioned whether

Matthew and his community were Jewish at all. After reflecting on this incident

and its aftermath, Matthew said, “The sad thing about this whole

matter is, that after forty or fifty years…they are planning ways of

discrediting all that it took us almost two generations to accomplish”

(Howard Waitzkin, “Black Judaism in New York,” Harvard Journal

of Negro Affairs 1967, 1.3).

In an effort to

circumvent Matthew’s leadership of the black Jewish community, a

“Committee on Black Jews” was created by the Commission on

Synagogue Relations. They in turn sponsored an organization called

Hatza’ad Harishon (The First Step), which attempted to bring black people

into the Jewish mainstream. Despite their liberal intentions, the project

failed because it was unable to navigate the same racial and ritual land mines

that Matthew had encountered. Matthew had written that “a majority of the

[white] Jews have always been in brotherly sympathy with us and without

reservation” (New York Age, 31 May 1958), but because he refused

to assimilate completely he met fierce resistance from white Jewish leadership.

As he explained,

We’re not trying to

lose our identity among the white Jews. When the white Jew comes among us,

he’s really at home, we have no prejudice. But when we’re among

them they’ll say you’re a good man, you have a white heart. Or they’ll

be overly nice. Deep down that sense of superiority-inferiority is still there

and no black man can avoid it. (Shapiro, 183)

Before Matthew’s

death at the age of eighty-one, he turned the reins of leadership over to a

younger generation of his students. Rabbi Levi Ben Levy, who founded Beth

Shalom E.H. Congregation and Beth Elohim Hebrew Congregation, engineered the

formation of the Israelite Board of Rabbis in 1970 as a representative body for

black rabbis, and he transformed Matthew’s Ethiopian

Rabbinical College

into the Israelite

Rabbinical Academy.

Rabbi Yehoshua Yahonatan and his wife Leah formed the Israelite Counsel, a

civic organization for black Jews. Matthew expected that his grandson, Rabbi

David Dore, a graduate of Yeshiva

University, would assume

leadership of Commandments Keepers Congregation, but as a result of internecine

conflict and a painful legal battle, Rabbi Chaim White emerged as the leader of

the congregation and continued the traditions of Rabbi Matthew.

Matthew and his cohorts were

autodidacts, organic intellectuals, who believed that history and theology held

the answers to their racial predicament.

Hence, their focus was not on achieving political rights, but rather on

discovering their true identities. They held a Darwinian view of politics in

which people who do not know their cultural heritage are inevitably exploited

by those who do. In this regard, Rabbi Matthew, Noble Drew Ali, and Elijah

Mohammad differ in their solutions but agree in their cultural

assessment of the overriding problem facing black people.

Further Reading

The largest collection of

papers and documents from Matthew and about black Jews is to be found at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New

York Public Library. Smaller collections are at the American Jewish Archives in

Cincinnati.

Brotz, Howard. The Black Jews of Harlem: Negro Nationalism and the Dilemmas of Negro

Leadership (1970).

Landing, James E. Black Judaism:Story of an

American Movement (2002).

Ottley, Roi. New World A-Coming: Inside Black America

(1943).

Shapiro, Deanne Ruth. Double Damnation, Double

Salvation: The Source and Varieties of Black Judaism in the United States, M.A. Thesis, Columbia University (1970).

* No part of these essays may be used without the

author’s permission.

Biography of Rabbi Yirmeyahu Yisrael

History of Kohol Beth B’nai Yisrael

and Bnai Adath Kol Bet Yisrael

By

Rabbi Sholomo Ben Levy

Rabbi Yirmeyahu

Yisrael

Rabbi Yirmeyahu Yisrael began life

as Julius Wilkins and used the name Wilkins during the early part of his

rabbinic career with Kohol Beth B’nai Yisroel and later with B’nai

Adath Kol Bet Yisroel. By

the 1960s, he used the name Yisrael, which is how he is best remembered. It is

believed that his parents migrated from the South, probably from North Carolina, to Harlem,

where Rabbi Yisrael grew up between WWI and the Depression. His mother was a

member of the Commandment Keepers Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation that was

founded by Rabbi W.A. Matthew in 1919 and was then located at 87 West Lenox Avenue. Many of the early members of Commandment

Keepers were followers of Marcus Garvey, including Rabbi Matthew’s

teacher, Rabbi Arnold J. Ford.

Rabbi Yisrael graduated from the Ethiopian Rabbinical College,

a private rabbinic institution founded by Rabbi Matthew in 1925, and was

ordained in 1940. According to Rabbi Hailu Paris, Rabbi Yisrael was very

intelligent, energetic, and ambitious. Within a few years of his ordination, he

felt that he was ready to start his own congregation, one where he could

implement changes to the community’s Judaic tradition that would bring

its liturgy further inline with those of white Orthodox Jews while maintaining

the strongly held belief that the original Jews were black people. For several

months individuals met in his home on seventh avenue before acquiring space for

their new congregation, Kohol Beth B’nai Yisroel, Inc., in the fall of

1945. Their synagogue was first located above a tailor shop and below a meeting

hall for the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) at 204 Lenox Avenue—just

a few blocks from Matthew’s similarly situated congregation. The fact

that approximately fifty members of Commandment Keepers eventually left to join

Kohol or actively supported it further added to the tension and sense of

rivalry that slowly estranged Matthew from his most dynamic student of that

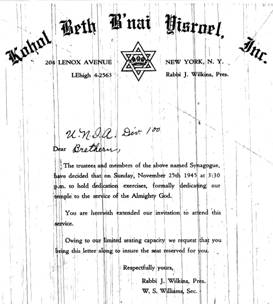

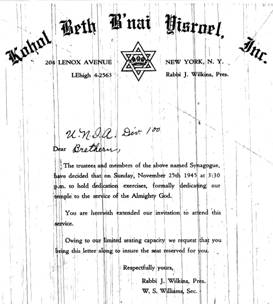

period. The following invitation to the dedication ceremonies of Kohol on 25

November 1945 was addressed to the UNIA Division 100 and was found in the UNIA

collection at the Schomburg

Center for Research in

Black Culture.

The program for the dedication ceremonies indicates

that they opened with Rabbi Ford’s

original composition “Sine on Eternal Light,” they then sang

Psalm 122. Bro. Philip Evelyn presented the key to the synagogue to Rabbi

Wilkins followed by Pslam 84. Other notable features include the singing of

“They that trust in the Lord,” “Now Thank We All Our

God” and “Glorious Things of Thee are Spoken.” They marched

around the synagogue seven times with the Torah which had been donated by

Eudora Paris and had a ceremonial lighting of the “Perpetual Light / Nir

Tamed.” The prayers that were said included the Kaddish by Rabbi L.

Samuels, the Shema, and the evening liturgy. An address was given by Rabbi E.J.

McCleod, who would later vie with Yisrael for control of the congregation. It

is also significant that the ceremonies included the singing of the national

anthems of America and that

of Ethiopia.

For almost ten years the new congregation grew

steadily but a rift gradually developed between the old guard, best represented

by Rabbi McLeod and the new guard, represented by Rabbi Yisrael. The minutes of a meeting that took place

on 1 July 1951, which is located in the Kohol Beth B’nai Yisrael

Collection SCM95 –27 /MG 575,

reveals that a primary area of contention

related to the content of their liturgy—particularly concerning

songs that were popular in the black Christian traditions of America and the

Caribbean and the nationalistic songs composed by Rabbi Ford. Rabbi Wilkins is

quoted as referring to the “unfitness for our service of some of the

numbers we sing.” It seems that Rabbi Yisrael and a large core of

supports were becoming uncomfortable singing songs that were strongly

identified with the black Church, even though none of the songs they used

referred to Jesus and most were drawn from the Old Testament Bible images that

characterize Negro spirituals. It is also likely that many of Rabbi

Ford’s nationalistic songs—particularly those that referred to

Ethiopia—were becoming passé by the 1950s; even members of the

Paris and Piper families who attempted to emigrate to Ethiopia in the 1930s had

become somewhat disillusioned. The songs, prayers, and customs that Rabbi

Yisrael wanted to replace aspects of the older tradition were often chants,

hymns, and practices that were popular in white Orthodox synagogues.

A split occurred shortly before 2 May 1954 because on

that date a meeting was called. The minutes from this meeting refer to

“cruel actions” taken by Rabbi Wilkins that were “out of

place.” It also indicates that Rabbi Wilkins “has discontinued his

service as Rabbi; he is demanding $2,000 and 2 Torahs and 50% of the Temple books.” The congregation continued under the

leadership of Rabbi McLeod for several more years. In January 1957 overtures

were made byRabbi Abel Respes who founded Temple Adat Beyt Moshe in Philadelphia in 1951 (the congregation later moved to Elwood, New

Jersey in 1962, chose to live communally, and

underwent a formal conversion to Judaism in 1971).

Rabbi Respes attempted to get Kohol to pursue new efforts to integrate with

white Jews. Rabbi C. Moses, who

founded Mt. Horeb

congregation in the Bronx 1945, was present at

this meeting and was troubled by Rabbi Respes reputation for soliciting white

Jews for financial support and Moses expressed grave concerns about how

receptive white Jews would be to them. Sister Paris cautioned the group that

“white Jewry has controversy within itself;” this remark most

likely refers to the deep theological division between the Orthodox, Reform,

and Conservative branches of American Judaism. Joining white Jews would require

taking sides with one of the main divisions.

Rabbi Yisrael’s second congregation,

B’nai Adath Kol Beth Yisroel, was located in Harlem

at 4 West 121 Street and was incorporated on 1 May 1954. Mrs. Myrtle Pilgrim was elected

Secretary of the congregation and Victor A. George was among the first ten

charter members. Unlike Kohol, B’nai Adath would attract newer, younger

followers who did not have prior affiliations with older black Jewish

congregations. Later in the year,

the congregation moved to modest accommodations at 131 Patchen Avenue in Brooklyn.

The congregation experienced rapid growth during the 1960s, growing to several

hundred members. Many of the new adherents were attracted to Judaism because of

the new wave of black consciousness that, like the Garveyment of the 1930s,

stressed discovering the true identity of black people. Around the mid 1960s,

B’nai Adath took possession of a huge synagogue building at 1006 Green Avenue

after the dwindling Orthodox community that built the edifice around the turn

of the century could no longer sustain it.

With the capacity of seating several hundred worshipers, B’nai

Adath became the largest congregation founded by one of Rabbi Matthew’s

students.

During the 1970s, B’nai

Adath served as the principal meeting place for a group of black rabbis that

included Rabbi Yisrael’s peers in Rabbi Woods and Moses, but also a third

generation of Rabbi Matthew’s students that included Rabbi Y. Yahonatan

(J. Williams), Rabbi Levi Ben Levy (L. McKethan), and Rabbi Paris, who had, in

fact, been Bar Mitzvahed by Rabbi Yisrael in 1947. In 1971 this group organized themselves

into the Israelite Board of Rabbis (IBR) and in 1973, the same year in which

Rabbi Matthew died, the IBR renamed their alma mater, the Ethiopian

Hebrew Rabbinical

College, to become the Israelite Rabbinical Academy.

Rabbi Yisrael was undoubtedly surprised and disappointed when the body elected

him to the post of vice president and chose the much younger Rabbi Levy to be

their president. Rabbi Levy has recently acquired a large synagogue at 730 Willoughby Avenue

in Brooklyn to become the home of Beth

Shalom. For the remainder of the

decade, Rabbi Yisrael remained a supporter of the IBR and encouraged the men

who would later succeed him at B’nai Adath to enroll in the Israelite Rabbinical Academy.

They were: Rabbi K.Z. Yeshurun, Rabbi Amasiah Yehudah, Rabbi Betzallel Ben

Yehudah, and Rabbi Cadmiel Ben Levy. Rabbi Yisrael was a world traveler who

sought out black Jews in Israel,

Ethiopia, and various

countries in West Africa. Rabbi Gershom,

leader of the Abayudaya, reports that Rabbi Yisrael left a lasting impression

on the black Jews or Uganda

during one of his early trips. Following Rabbi Yisrael’s retirement in

the early 1980s, Rabbi Yeshurun become the spiritual leader of B’nai

Adath. Rabbi Yisrael and his wife Cora retired and spent most of their

remaining years in the 1980s

traveling and living abroad in the Virgin Island.

* No part of these essays may be used without the

author’s permission.

Biography of Rabbi Levi Ben Levy

History of Beth

Shalom and Beth Elohim

By

Rabbi Sholomo Ben

Levy

Rabbi Levi Ben Levy

1935-1999

Chief Rabbi Levi Ben Levy was

one of the most dynamic black rabbis in America. He provided vital

leadership for his people during the second half of the twentieth century as a teacher,

speaker, community-organizer, founder of synagogues, and builder of

organizations. Together with his many colleagues, he provided continuity with

the past by preserving the work and memory of his teacher and our founder,

Chief Rabbi W. A. Matthew. By

combining vision with action, Chief Rabbi Levy helped to define who we were as

a people and greatly influenced the direction of our progress. His

accomplishments completed part of our foundation. Therefore, an understanding

of his live is necessary to anyone who wants to know and appreciate our

history.

This great leader was born on

February 18, 1935 to a God-fearing family in Linden, North Carolina.

It was there that he met and married his childhood sweetheart Deborah Byrd. In

1950, he came to New York City.

After managing a restaurant and attempting a small business, the young Rabbi

Levy enrolled at City

College in 1957. He took

courses at night while working for the Long Island Railroad to support his

growing family. At this point, however, the hand of fate altered his path when

his friend and coworker, Mr. Arnold Manot, invited him to attend the

Commandment Keepers Congregation in Harlem,

New York. It was there that he

met the person who had the most profound affect on his life, Chief Rabbi

Matthew. First, Rabbi Levy became a member of the congregation, then he was

invited to joins its secret society called “The Royal Order of Ethiopian

Hebrews Sons and Daughters of Culture.” After completing his Hebrew

studies, his teachers and the mothers of the congregation, encouraged him to

enter the Ethiopian

Hebrew Rabbinical

College in 1960. Through

much hard work, sacrifices, and challenges he graduated six years later and was

ordained by Chief Rabbi Matthew with great public acclaim in 1967.

Immediately upon graduation and

ordination, Rabbi Levy knew that he was destined to do great things. He was

trained and equipped with the truth to awaken the “lost House of

Israel.” With Chief Rabbi

Matthew’s blessing, Rabbi Levy started his first congregation, which he called

Beth Shalom, in the living room of his Queens

apartment with only eight members. For the first few years, as increasing

numbers of people wanted to worship with them, they rented halls at various

locations before acquiring their first building at 609 Marcy Avenue in Brooklyn, N.Y.

In 1968, Rabbi Levy negotiated an

arrangement with the Young Israel of Williamsburg that allowed him to move his

congregation into the present home of Beth Shalom E. H. Congregation at 730 Willoughby Avenue.

In

1971, Rabbi Levy together with Rabbi Yisrael, Rabbi Yahonatan, Rabbi Woods, and

Rabbi Paris—all students of Chief Rabbi Matthew—set out to revive

their alma mater, the Ethiopian Hebrew Rabbinical College that was established

in 1925. They expanded the curriculum and renamed their college The Israelite

Rabbinical Academy. As other rabbis joined their ranks, and eager, dedicated

men enrolled as students, a unified organizational body emerged which was first

known as the Israelite Board of Rabbis and later, after establishing boards and

chapters in other cities and then in Barbados, became the International

Israelite Board of Rabbis. Four years after the death of Chief Rabbi Matthew in

1973, the rabbis of the International Israelite Board of Rabbis elected Rabbi

Levy to be the next “Chief Rabbi.”

In 1983, Chief Rabbi Levy

founded his second synagogue, Beth Elohim Hebrew Congregation, in Queens New

York. In 1988, he installed his eldest son, Rabbi Sholomo Levy as the Spiritual

Leader of the Congregation. Throughout the 1990s, Chief Rabbi Levy provided

counsel and direction to those who sought his wisdom from his retirement home

in North Carolina.

Amazingly, Chief Rabbi Levy

managed to enjoy a full and wholesome family life despite his endless

commitments and obligations. He and his wife, Deborah, were partners in love

and life. Their marriage of over forty-six years produced six children:

Deborah, Yehudith, Tamar, Zipporah,

Sholomo, and Benyamin. At the time of his passing, he had nine grandchildren

and many nieces, nephews, and God-children.

Chief Rabbi Levy gave honor to

God and distinguished himself by founding two thriving congregations, Beth

Shalom and Beth Elohim, an educational institution in the Israelite Rabbinical

Academy that has produced most of the black rabbis in America, a unified

leadership organization in the International Israelite Board of Rabbis, and

gave us a quality publication in the The Hakol newsletter, and the first

Israelite presence on the Internet. During his life, he received dozens of

awards, plaques, and citations. He ran a half-hour radio program on radio

station WWRL, he appeared on television programs such as “Black

Pride,” and “Good Morning America” and he spoke to audiences

internationally. For all these accomplishments and more, Chief Rabbi Levy is

remembered as one of our greatest rabbis.

* No part of these essays may be used without the

author’s permission.

List

of Black Rabbis in America

|

Living Black Rabbis

|

Rabbis of

Blessed Memory

|

|

Avraham Ben Israel

|

Abihu Ruben

|

|

Baruch Yehudah

|

Amasiah Yehudah

|

|

Benyamin B. Levy

|

Arnold J. Ford, First Rabbi

|

|

Bezallel Ben Yehudah

|

B. Alcids

|

|

Calib Yehoshua Levy

|

C. Harrel

|

|

Capers Funnye

|

C. Woods

|

|

D. Yachzeel

|

Chaim White

|

|

*

Daton Nasi

|

Curtis Hinds

|

|

David Dore

|

D. Small

|

|

Eliezer Levi

|

David Levi

|

|

Eliyahu Yehudah

|

E. M. Gillard

|

|

Hailu Paris

|

E.J. Benson

|

|

* James Hodges

|

G. Marshall

|

|

Joshua

Ben Yosef

|

H.S. Scott

|

|

K.Z. Yeshurun

|

James Bullins

|

|

Lehwi Yhoshua

|

James Y. Poinsett

|

|

Nathanyah Halevi

|

Jonah

|

|

Richard Nolan

|

Kadmiel Levi

|

|

Shelomi D. Levy

|

L. Samuel

|

|

Sholomo B. Levy

|

Lazarus

|

|

Yehoshua B. Yahonatan

|

Levi Ben Levy, Chief Rabbi

|

|

Yeshurun Eleazar

|

M. Thomas

|

|

Yeshurun Levy

|

Matthew. Stephens

|

|

Zacharia Ben Levi

|

Moses

|

|

Zakar Yeshurun

|

Patiel Evelyn

|

|

Zidkiyahu Levy

|

Raphael Tate

|

|

|

W. O. Young

|

|

|

Walcott

|

|

|

Wentworth A. Mathew, Founder

|

|

|

Yirmeyahu Ben Israel

|

* Rabbis who graduated from institutions

other than the Israelite

Rabbinical Academy

This list only covers members of the International Israelite Board of

Rabbis

** Honorary

Titles

|

|

* No part of these essays may be used without the

author’s permission.