Ethiopian Jews Seek Unity With All Black Jews

Rabbi Sholomo Ben Levy

In June we received a letter from two prominent Ethiopian leaders in Israel: Chief Kess, Rafael Takoya Hadane and his son Yosef Hadane—who is the Ethiopian Israeli Chief Rabbi. They congratulated Chief Rabbi Capers Funnye on his inauguration, reaffirmed Africa’s ancestral connection to the biblical Israelites, and expressed a desire for mutual cooperation. They said to us, “In this spirit of unity and brotherly love, we come together with you now, to honor this great leader, Chief Rabbi Funnye, in celebration of Black/African Jewry’s rich, diverse past and looking forward to the promising future of Black/African Jews.”

The last time there was a high-level meeting between Ethiopian Jews and African American Jews was on December 23, 1931. At that time Taamrat Emmanuel (1888-1963)—an Ethiopian spokesmen who was educated in France and Italy—was brought to the United States on a fund-raising tour sponsored by a group called the “Pro-Falasha Committee.” Despite their use of the derogatory term “Falasha,” which is anathema to Ethiopians who called themselves “Beta Israel,” this group of liberals strongly discourage Mr. Emanuel from contacting Chief Rabbi W.A. Matthew and visiting Commandment Keepers Congregation in Harlem. As ludicrous as it seems now, Dr. Norman Salit, Chair of the American Pro-Falasha Committee, was attempting to propagate the notion that Ethiopian Jews were actually the offspring of White Jews whose skin had darkened as a result of prolonged exposure to the sun. The Pro-Falasha committee argued, correctly, that Ethiopian Jews needed to be saved from Christian missionaries who had converted Mr. Emanuel’s parents. Dr. Salit had denounced Rabbi Matthew’s form of Judaism as being inauthentic and urged Mr. Emmanuel to avoid contact with Negroes during his visit. In a sense, the Pro-Falasha committees of the world believed that only their form of Judaism was legitimate.

At that time, association with other Black Jews was politically dangerous for Ethiopians. The State of Israel had not yet been created, so Ethiopians did not fear being denied immigration. However, Mr. Emmanuel’s primary mission was to raise money for a school in Ethiopia. Therefore, it required an act of courage for Mr. Emanuel to seek out his brothers in Harlem. The transcript shows that he spoke in French through a translator. He told Chief Rabbi Matthew that he felt a natural kindship with the struggling Black Jews of Harlem. Rabbi Matthew reciprocated by pledging his support for Ethiopia—a commitment he honored through his support for Rabbi Ford’s pilgrimage to Ethiopia in the 1930s. For his part, Mr. Emmanuel struggled for the rest of his life to gain recognition and acceptance for Ethiopian Jews. He also tried to find the proper balance between rabbinic Judaism and preserving Ethiopian culture and tradition. He started a school called the Hebrew Institute for this purpose. Our beloved Rabbi Hailu Paris זצ״ל attempted to continue Mr. Emmanuel’s work. In the end, Mr. Emmanuel drifted away from the controlling influence of his mentor Dr. Jacques Faitlovitch and accepted a diplomatic post as “cultural attache” to His Majesty Haile Selassie.

In August, the Ethiopian delegation will be represented by Qes Eli Mentessnout, Mr. Shmuel Legesse, and other Ethiopian Jews residing in the United States. The process of unification that began 85 years ago with be strengthened at the International Israelite Convention. The Israelite Board of Rabbis renews its commitment to support, defend, and advocate for Black Jews all over the world. Chief Rabbi Funnye looks forward to meeting the Chief Kes and the Ethiopian Chief Rabbi during his next trip to Israel.

Further Reading

Yosef Ben-Jochannan, We the Black Jews (Black Classic Press, 1993); Sholomo Levy, “Biography of Rabbi Arnold Josiah Ford,” Blackjews.org, February 24, 2016, http://www.blackjews.org/biography-of-rabbi-arnold-josiah-ford/; Jody Benjamin, “A Visitor From Ethiopia Discovers Harlem,” Tadias Magazine, August 23, 2008, http://www.tadias.com/index.php?s=Taamrat; William S. Scott, The Sons of Sheba’s Race: African-Americans and the Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935-1941 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993); Winston James, Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia (New York: Verso, 1998); Ephraim Isaac, The Question of Jewish Identity and Ethiopian Jewish Origins.: An Article from: Midstream, n.d.; Leonard Lyons and Ilan Ossendryver, The Ethiopian Jews of Israel: Personal Stories of Life in the Promised Land (Woodstock, Vt.: Jewish Lights Pub., 2007); William Scott, “The Ethiopian Ethos in African American Thought,” International Journal of Ethiopian Studies 1, no. 2 (January 1, 2004): 40–57; William R. Scott, “Rabbi Arnold Ford’s Back-to-Ethiopia Movement: A Study of Black Emigration, 1930-1935,” Pan-African Journal 8 (1975): 191–201; Emanuela Trevisan Semi, “From Falashas to Ethiopian Jews: The External Influences for Change C. 1860-1960,” Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 24, no. 2 (Winter 2006): 200–202; Emanuela Trevisan Semi, Jacques Faitlovitch and the Jews of Ethiopia (London; Portland, OR: Vallentine Mitchell, 2007); Bahru Zewde, “The Ethiopian Intelligentsia and the Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935-1941,” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 26, no. 2 (January 1, 1993): 271–95, doi:10.2307/219547.

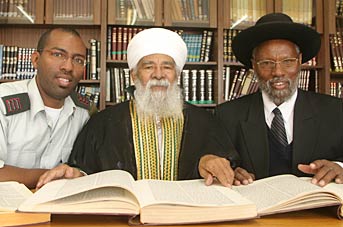

Photo Credit

Used by permission: photo by Ilan Ossendryvr, from the book, The Ethiopian Jews

of Israel: Personal Stories of Life in the Promised Land by Len Lyons

Link to Ethiopian Letter to Chief Rabbi Funnye