A Closer Look at Chanukah

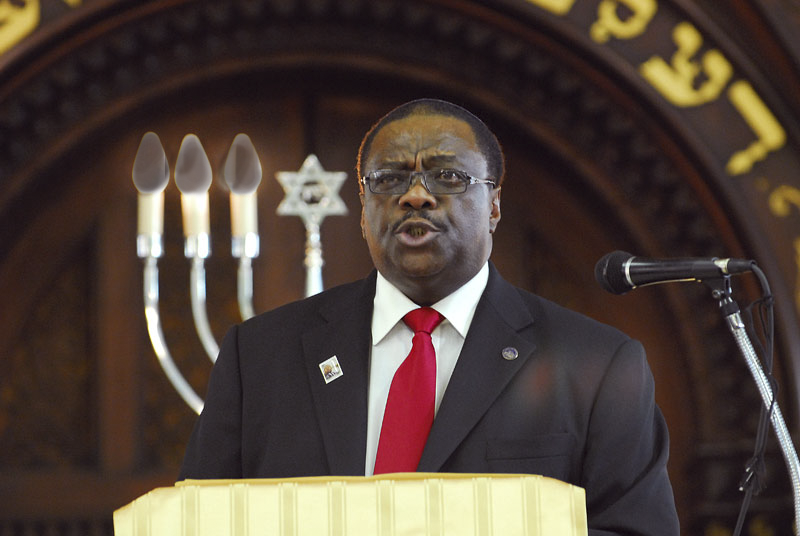

Chief Rabbi Capers Shmuel Funnye

22nd Kislev, 5779 – November 30, 2018

Chanukah is just around the corner. In fact, we light the first candle on Sunday evening. Chanukah is in many ways the chag of religious striving, of religious maximalism. When Hellenism permeated the land of Israel, many Israelites fully embraced it. They were not deeplyor profoundly committed to a life of Torah and mitzvoth. They were not interested in struggle and in striving to see this ideal achieved. Torah was a lifestyle, not a passion, and they were happy to adapt, to be complacent, to go with the flow. When Antiochus demanded that the people worship pagan gods, desecrate the Shabbat, and refuse to circumcise their sons, many lacked the inner strength and conviction to resist. It was only Matityahu, with his cry, “Let everyone who is passionate for the Torah come after me. ( I Maccabees 1:27)” Only Matityahu with his depth of commitment and passion, was able to inspire and lead the revolt that ultimately culminated in the defeat of the Seleucid-Greeks, the recapturing of the Temple, and the miracle of Chanukah.

And, so, Chanukah is the chag of religious striving, of rejecting a disposition of complacency and passive acquiescence. It is thus that we find that the laws of martyrdom were crystallized at the time of Chanukah, at the time when so many were willing to sacrifice their lives because they realized that there was more to life than just getting along; that there was something of ultimate and transcendent value, something worth giving up one’s life for.

However, such passion can also be dangerous. It can lead to a dismissal of human realities and human concerns. All that is important is the ideal, the vision. We find sometimes that activists for causes can act in obnoxious or unethical ways to the people around them. For them, only the cause matters-real people are insignificant. This actually was an early misstep of the Maccabees not to be inappropriately dismissive of others’ lives, but of their own. We read that when they were attacked on Shabbat, they refused to fight and defend themselves, and were slaughtered in great numbers. It was then they realized that serving G-D required attending to the lives and realities of human begins as well:

“And one of them said to another, if we all do as our brethren have done, and fight not for our lives and laws against the heathen, they will now quickly root us out of the earth. At that time, therefore, they decreed, saying. Whosoever shall come to make battle with us on the Shabbat day, we will fight against him; neither will we die all, as our brethren that were murdered in the secret places.” (I Maccabees 2:40-41)

They intuited that it was G-D’s will that Shabbat can and must be violated to save a human life, a ruling that was later endorsed and given proof texts by the Rabbis.

So where does all of this leave Israelites today? I believe that our community must examine, discuss, and possibly change many of the current traditions that hold sway in the Israelite community. When will we actively engage in the process of the creation of a Halakah for the Israelite community? Hag Chanukah!