This is a year of return. Four hundred years ago, in 1619, the first African stepped onto the shores of Jamestown, Virginia. In many ways, that event was more significant than landing on the moon. In fact, one could argue that if those Africans had not proceeded to make the colonies rich, our history would be very different—if it existed at all. People have always wanted to measure time. Ancient man looked up at the night sky and began counting the number of days to complete the phases of the moon; that gave us months and eventually years. We poured sand through an hour-glass to achieve more precision. The strange thing about time is that even our most advanced clocks are instruments that can only measure the passage of time from some point in the present to some other point in the past. Nothing measures time in the future. And as we look back, we see patterns and cycles that seem to repeat; markers and turning points that tell us how low we sunk and how far we have come. This year is such a time of reflection.

As fate or chance would have it, 2019 was the year that I touched the shores of West Africa for the first time. Hence, I completed a generational cycle that took 400 years or sixteen generations to close. I witnessed the greatness of Egypt many years ago and remind people that Egypt is Africa’s oldest civilization; but in my heart, I knew that I had not truly seen Africa until I set foot on the soil from whence my ancestors departed. From the comfort of the departure terminal of JFK airport in New York City, I allowed myself to wonder what my ancestor thought as he or she sat chained, hungry, beaten, and crammed into the hull of a wooden ship. The contrasts were stark: I was excited and bursting with anticipation for this journey; they, no doubt, were terrified as they looked and prayed in vain for a way to escape their journey of horror. I wore my favorite blue blazer and a natty Panama hat that always identifies me as a tourist. Four hundred years ago, I wore shackles on my wrists instead of an Apple Watch and chains around my neck instead of the thin wire connecting the earbuds of my soft headphones. Because Northampton Community College was sending me on this academic mission to access the feasibility of a study abroad course, I knew that I was privileged. Then, I must have felt like one of the most forsaken people in the world; chosen to be a slave. Indeed, I have lived vicariously through my ancestors as surely as I will continue to live through my children and their posterity. Over those generations, I have been a beast of burden, chattel property, a Nigger, and second class citizen before becoming the person that I am today.

When I arrived in the capital of Accra, I expected the landscape to be filled with lush, green trees. After all, I had been told that the color green in the flag of Ghana and in the Black Liberation Flag represented the verdant land. Instead, what I saw in this thriving metropolis was a concrete jungle of buildings, stores, roads, and churches everywhere that seemed to be growing from places where trees once stood.

I lodged at a comfortable guest house owned by Dr. Kobla Agbota, a Ghanaian professor who teaches at Oslo Metropolitan University in Norway and lives in Europe with his Norwegian wife. Kobla took me for pleasant walks through the neighborhood and the local market. I was impressed by how open and friendly the people were. The variety and abundance of produce were amazing. Some mornings Kobla prepared meals where I tasted fruits and vegetables that I had never eaten before; things that had strange names, exotic tastes, and wonderful fragrances. The sheer number of tiny shops, street vendors, and merchants who literally balanced their stores on their heads was a testament to the strong entrepreneurial spirit that abounds in Africa. Everyone feels empowered to start a business—from the girl who sells boiled eggs to the kiosks peddling cell phones and calling cards. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much that I could see that distinguished this admirable work ethic from modern capitalism and material consumerism—except that people in Africa went about their business in a more relaxed manner.

Professor Kobla explained that he and most of the people we met in that area were members of the Ewe tribe. There was also a large population of Gha and Fante people in the region. Later in my trip, I would encounter the once-mighty Ashanti people of the Akan nation. All of these people spoke English because Ghana had been an English colony called the Gold Coast until 1957. Most of them spoke an African language called Twi. I enjoyed learning a few phrases in Twi from my driver, George. He taught me to say Akwaba (Welcome), Et Ta Zain (How are you?), Ah Yea (Fine), How Sway (And you), Ma Da Say (Thank You), and Ah Fey (Beautiful). On Saturday night Kwesi Acquah, the person who organized the tour who everyone called Prosper, took me to a popular nightclub where I expected to experience live African drumming and singing. For weeks prior this journey I had been listening to an old album by Babatunde Olatunji entitled “Drums of Passion” and the soul-stirring music of the South African singer Miriam Makeba. But, at this club—and as it turned out all over Ghana—the music I heard most at restaurants, on radios, and television was Jamaican Reggie and American Hip Hop.

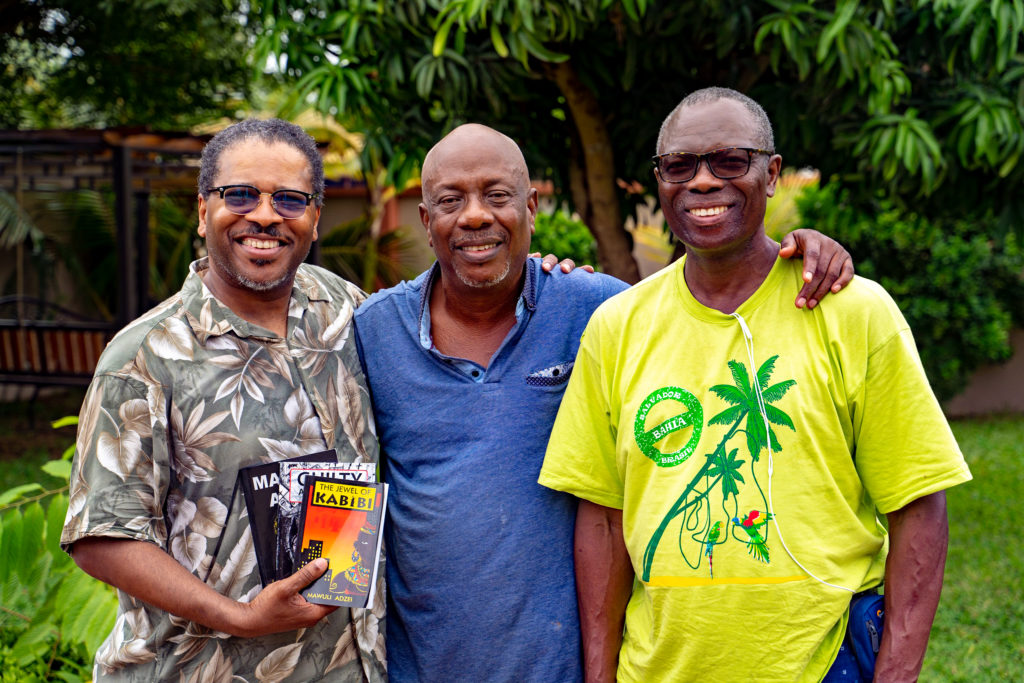

Two of the most remarkable people I met in Accra were a father and son duo: Mawuli Adzei, a novelist and poet and Sela Adjei, a talented young artist. Their work explores African themes and sensibilities. For example, Mawuli’s collection of short stories entitled Guilty As Charged, turns a critical eye on religious charlatans and corrupt politicians who threaten the cohesion of Ghanaian society. Filaments, is a collection of poems that expresses the African spirit with beauty and power. Both of these books are adorned with his son’s masterful artwork. If they lived in America, Canada, or the UK, their genius might be better appreciated. Over dinner, Sela told me that he is aware of the opportunities that exist for him in the West and that he plans to accept occasional fellowships and exhibits; however, he sounds fully committed to building up the artistic milieu of his beloved Ghana.

At the Univesity of Ghana, I had a meeting with Dr. Kodo Senah in the Sociology Department. He had lectured recently at Lehigh University and was, therefore, one of the few people who was familiar with my area of Pennsylvania. We spoke at great length about building bridges that will allow greater student interaction between Ghana and the United States. Principally this could take the form of study abroad opportunities for our respective students and—with the use of modern technology—joint conferences and live class interactions. Dr. Nathan Carpenter, who directs our Center for Global Education, provided me with a supply of brochures, pens, and USB drives that I presented as gifts to the many eager students that I met during my tour of their spacious campus. I found the students to be highly intelligent and seriously interested in learning more about ways to study in the United States. For several years now, the State Department has recommended Northampton Community College as an affordable institution where students receive an excellent education. Our experience with students from various African countries has been that they are academically well prepared and highly motivated students who enrich our campus with their unique perspectives.

Eating in Ghana was a very pleasing culinary experience. George seemed to know all the best places where locals go to eat. I was anxious to try a dish called Fufu because one of the travel books I read about Ghana jokingly advised women that if men proposed marriage on the street, they should decline. If asked, “Why won’t you marry me?” they should say, “Because I can’t make Fufu.” The point being that no Ghanian man would ever marry a woman who could not make this dish. I discovered that Fufu is actually several dishes. First, you are given a bowl in which to wash your hands. The Fufu is a large white ball made from a starch called yam or cassava. Traditionally, women would pound this tuber with a large mortar and pestle before it could be made into dough. Now there are machines that can spare women hours of this laborious task. The proper way to eat this dish is to take some of the Fufu with your right hand (use of the left hand for eating or exchanging things is a serious faux pas) and dip the Fufu into a bowl of soup that can be made with okra, pepper, or peanut. Other variations include fish, goat, or “bush meat.” Another popular dish in the same family was a stew called Banku. However, my favorite dish by far was Jollof Rice with roasted Tilapia; because these fish were caught in the ocean rather than farm-raised, they were bigger and more delicious than any I ever tasted before.

W.E.B DuBois, that towering African American intellectual and one of the founders of the NAACP, had been my hero since I read The Souls of Black Folk during my freshman year at Middlebury College. At Yale, I wrote my master’s thesis about his relationship with the Jewish activist Joel E. Spingarn. At Harvard, I worked for the W.E.B. DuBois Institute as an editor of the African American National Biography, which was the fulfillment of one of his dreams. And when I take my students on walking tours of Harlem, we visit the building where he and Supreme Court Judge Thurgood Marshall once lived. DuBois left the United States and lived in Ghana until his death in 1963. Visiting his home and final resting place was a sacred pilgrimage for me. I spent that day with Dr. Kwame Essien, the Lehigh University Africanist whose initial inquiries in the Spring of 2019 set this journey in motion. Shortly after our arrival, we spotted Professor Smalls from the City University of New York leading a group of young people on a tour. In the short time that we were there, we saw one tour bus after another loaded with African Americans of all ages who came, like me, to pay homage to DuBois. While I was disappointed to see that the Ghanaian government had not maintained the home, nothing can compare with the awe of standing in DuBois’s office, looking at this desk, personal affects, and the books in his fabled library. Occupying the same space of someone you admire—even if at a different moment in time—allows you to form a spiritual connection. Certainly, I felt as close to DuBois there as I will ever be.

The mausoleum erected to honor Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, reminded me of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington; i.e. it is stately and entirely appropriate for the accomplishments of the man. The things that troubled me most about the tour and in my subsequent debates with Professor Essien, is how Ghanaians minimize the fact that they deposed Nkrumah in a coup in 1966. Nkrumah lived in exile until his death in 1972. During that period there was no popular uprising to challenge Nkruma’s removal from office nor was there a movement demanding his return until after his death. Today Nkrumah is venerated all over Ghana. His face is on the money. There are streets, statues, and buildings named after Nkrumah. To my mind, this proves the biblical saying that a “prophet is never honored in his own country”—at least not until he is dead and safely buried. Then everyone can claim to have been die-hard supporters. In this regard, Nkrumah bears a lot of similarity to Lincoln, Kenndy, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia.

I learned a lot about the history and consequences of economic development in Africa at the Akosombo Dam on the Volta River. With this source of hydroelectric power, Ghana, Togo, and Benin were on course to becoming energy independent in 1965. Sadly, these countries grew so quickly that they required importing fossil fuels to meet the demands of modernization. The effects of global climate change are going to devastate Africa and their consumption of carbon is contributing to the problem. At the Auburn Botanical Gardens and Kakum National Park, I saw efforts to preserve some of Africa’s rainforests and protect the natural habitat of some of its wildlife. The baboons that crossed the road did not look as good as those I’ve seen in zoos. Yet, as we traversed the country, I was struck by the number of trucks that were dangerously loaded with sacks of charcoal, which many Ghanaians still use as a source of fuel. George and I would often make unscheduled stops along the road. We enjoyed buying roasted corn cobs or drinking coconut water from the vendors that dotted the countryside. Near

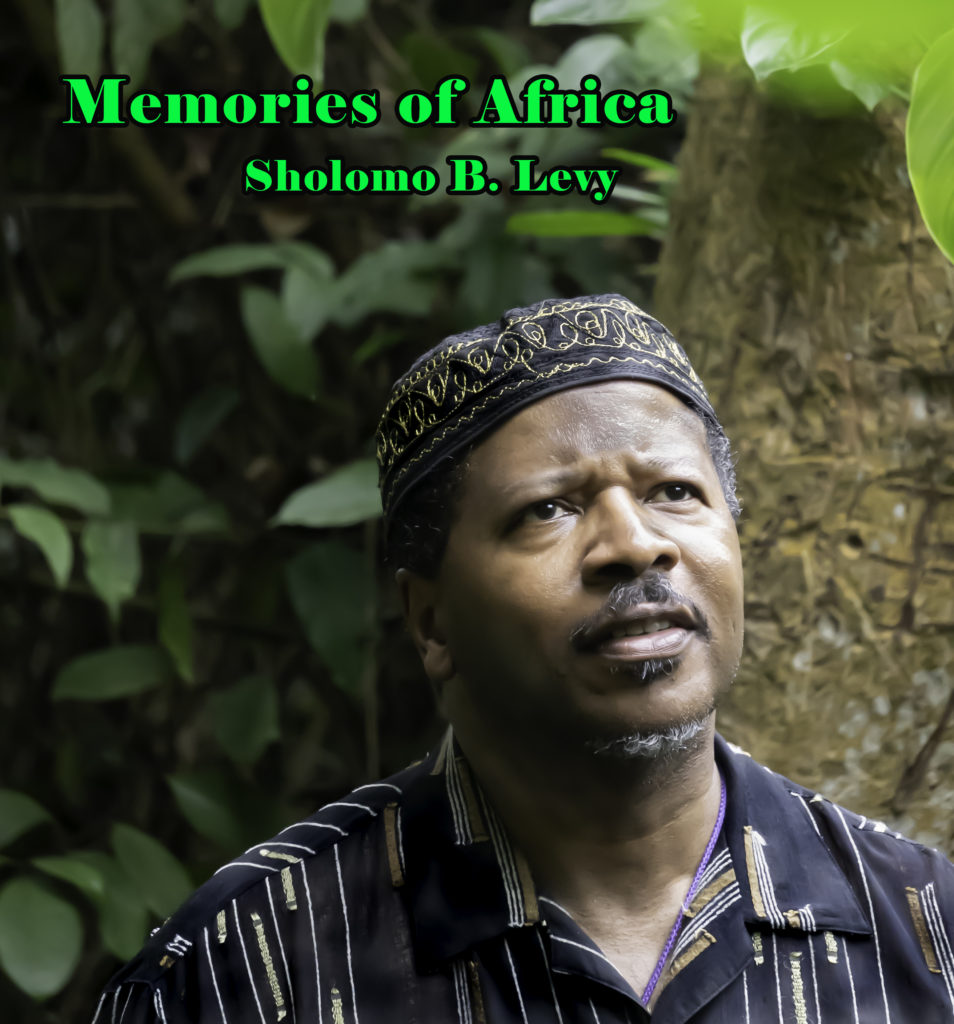

The most moving stop on my journey in Ghana was to the Slave Castle Dungeons in Cape Coast. Before I boarded my plane at JFK, I called Lauren Banner; we call him Popo and he was my childhood big brother. More importantly, he was a role model who imbued me with love for Africa. I told him that I was on my way to “The Motherland.” His advice to me was, “Don’t hold back the tears when you get to the slave castles.” As we drove east from Accra, the Atlantic ocean slowly came into view. By this point, I had become accustomed to the poor street peddlers who swarmed around cars at tolls, checkpoints, and intersections. I informed my companions that when we reached the Cape I had a dear friend from the states who would conduct the tour. They already knew Rabbi Kohain Halevi. He has a reputation in the land and his name is golden. Rabbi Halevi grew up in Mt. Vernon, New York, and led a synagogue there until he emigrated to Ghana over twenty years ago. Since then he has become a leader of a growing exile community of Black people from the United States and the Caribbean. They own a charming resort on the beach. Many of them have built homes in their area, which has become a most welcomed American enclave.

Rabbi Halevi was busy making plans for Panafest 2019. The president of Ghana and many of its chiefs were planning to commemorate the four hundredth anniversary. Like the Nkrumah statues, the festivities for African Americans would focus on how much our African brothers loved us and very little about how they sold us. But, such are family reunions. After purchasing our tickets, we mulled around the entrance to the slave castle dungeons. I was no longer anxious to see what was inside. It was like visiting a crime scene—except without the yellow tape and calk drawings that outline the bodies of our murdered relatives. No. Each blood-stained brick of this place qualifies as a tombstone.

Unlike Elmina Castle, which was built earlier and designed to store a variety of goods, architects designed Cape Coast Castile for the primary purpose of holding slaves. Therefore it represented the state-of-the-art, custom-made, people processing plant. Men and women were separated and held in cavernous dungeons beneath the fort. All possibilities of escape were cut off. Only enough air and light penetrated the bars on the small windows to prevent suffocation. When business was good, enslaved people were packed so tightly that there was not room enough to lie down. They were forced to stand in their urine, feces, vomit, and menstrual flows. They were only cleaned before being raped or sold. When the slave ships arrived, captains paid the chiefs or their European middlemen. In these negotiations, the buyer knew that the value of these human lives was greater than the guns, rum, beads, and trinkets that the African dealers accepted in exchange. The buyers were very selective. They chose the best, the strongest, those most likely to survive the voyage. Their human cargo was tightly bound, hustled through the “Door of No Return” and packed like sardines in the hull of a ship. The ship would then continue down the African coast to the next castle and repeat the process until its hole was full to capacity. Depending on the winds and design of the vessel, enslaved people might be chained in this position for three to eight weeks before reaching a port in the Caribbean. The lucky ones died and were fed to the sharks. Those who survived were condemned to being slaves for the rest of their lives.

From deep within the tombs of the slave castle, you can hear the thunder of the ocean’s waves pounding against the foundation of the fortress. In their regularity, the pounding of the waves sounds like a heartbeat; but, in their occasional ferocity, they evoke the image of God’s fists pounding on the door.

As we sat on the ramparts of the castle, I noticed how all of the canons faced the sea. This told me that the fort was built with the permission and support of the local tribes. The canons were not facing inland because there were no African armies coming to rescue us. The canons were intended to defend the fort from rival European powers who fought each other for control of the lucrative slave trade. The Portuguese and the Spanish were the first. In the end, it was the British who came to dominate the slave trade–and with that trade–much of the world. Prayers were made as we stood on a narrow platform between the “Door of No Return” and the ocean. Kohain gave me a special blessing for “Those Who Have Returned.” I blew a shofar (ram’s horn) that I acquired in Israel and recited a prayer we composed during Passover several years earlier in memory of the Israelites who migrated across the African continent and were then sold again into slavery as foretold in Deuteronomy 28. Chief Rabbi W.A. Mathew, the founder of our community, devised a tradition for us to perform during the holy days of Rosh Hashanah (Yom Zikron- Day of Remembrance) and Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement.) The Chief Rabbi instructed our people to deposit small silver coins in a bowl of anointing oil in substitution for the biblically required offerings, which we did not have. The coin representing the sin offering was to be cast away, like the scapegoat in ancient times. This year I carried one of those coins with me from America. From the rocky coast of this slave castle, I threw that coin into the depths of the sea. (Video)

We were only in the tombs for a few minutes, but it felt like hours. As we ascended, we felt the sun on our faces. The ocean breeze dried my tears and blew away the sense of claustrophobia that had surrounded me. Immediately, we felt thankful to be free and outside. Kohain Halevi stopped us and asked us to turn around and observe the building that stood directly above the dungeon. It was a church. It had been the fort’s chapel, the place where the people who operated the machinery of cruelty came to find spiritual relief, absolution, and, indeed, divine justification for all their sins. When Kohain made his home in this area, he said the castle had fallen into a state of disrepair. That abandoned chapel was then being used as a bar for locals and tourists. The bar was as much a desecration as the church that preceded it. After petitions and a protest where Kohain and other conscientious objectors staged a fast and occupation of the dungeons, the bar was finally moved and the process of converting this crime scene into a memorial began in earnest. In 2009, President Barack Obama and First Lady Michele Obama placed a plaque on the wall and pledged that the world would never forget what happened during the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.

When my ancestors were taken from these shores, they wondered if they, or the descendants, would ever return. Now that I have returned I, too, wondered about its deeper meaning. Nearly all of the enslaved people were sold in the Caribbean and Brazil. Less than one percent of the many millions of Africans were sold in the American colonies. Yet, four hundred years later, the descendants of that one percent have grown to a population of over thirty million people. As a group, African Americans have more collective wealth, higher levels of education, standards of living, and political power than any other population of Black people on this planet.[1] The irony of these facts has not been fully understood—particularly by African Americans —who have not considered the possibility that they were chosen for some special purpose and might have some cosmic destiny to fulfill. By virtue of being in the wealthiest and most powerful country in the world, African Americans are in a unique position to affect change. These are the thoughts that ran through my mind.

My final stop on this journey was to Kumasi, the home of the Ashanti people who once ruled this land. We traveled many hours over crumbling and unpaved roads before reaching the grand palace of the Ashantihenna. This mansion was built by the British in 1925 in reparation for the original place, which the British destroyed during their attempts to conquer the Ashanti people. From the moment you enter the wide courtyard and see the statues honoring their great kings and queens, the emblems of their royal clans, and the peacocks that still walk the grounds, you realize that these African chiefs enjoyed the same level of respect as the kings of Europe. The symbol of the Ashanti people is a golden stool, which legend says fell from heaven. Each chief has a unique stool carved for his inauguration. The Ashanti people weave a beautiful cloth that is highly valued and often imitated. George took me to the nearby village of Bonwire where a group of skilled artisans continue to make Kente fabrics using the traditional foot-powered looms. The weavers were all men. One of the craftsmen explained that pregnancy would make it impossible for women to operate the tight looms and there are other prohibitions. They kindly invited me to try operating one of the more simple looms. It reminded me of trying to sit on a bicycle while coordinating these quick motions with both your hands and feet simultaneously. After a few minutes, I developed a great appreciation for the skill required to produce these fabrics. Once they are made, they are taken to markets and shops where women run most of the businesses. The Akan people refer to this fabric as Nwentoma, which means woven cloth. Cheap imitations of this fabric can be easily identified because the colors and patterns are printed onto the cloth rather than woven into it by hand.

I purchased several strips of Kente cloth and a smock for men that most people would call a “Dashiki,” but that word more accurately refers to a top made by the Yoruba people of Nigeria. Back in Accra, I had several dresses made for the women of my family. The seamstress there demanded to know how I was related to each woman. She asked, “Are all these women your wives?” I said, “No, one is for my wife, one for my mother, and the others are for my sisters.” Therefore, she explained, all these dresses cannot be the same style—even though they are made with matching fabric. The mother and the wife must be distinctive according to African tradition. Another disturbing fact that I learned at this dress shop is that most of the fabrics sold in Africa and around the world are actually printed in China and Holland. In America, we argue that labor costs are cheaper in undeveloped countries; but in Ghana, there is an abundance of cheap labor. Yet, China can mass-produce African style fabrics cheaper than Africans. I also heard the sentiment that the Chinese build better roads because they have more expertise and far less corruption. Hence, much of the construction going on in Ghana is done by foreign companies who merely use local labor.

My return flight stopped in Morocco. Geographically it was as far north as one could travel in Africa before reaching Europe. From that point on a map, it looks like Africa and Europe are close enough to kiss each other. Yet culturally they are worlds apart. While I felt comfortable in West Africa because of my blackness and ancestral connection, I realized that they would never see me as an African like them—even if I could lose my accent and change my citizenship. Cultural identity is more than skin deep. Printed on my boarding pass were the words “Destination New York.” Etched in my mind was the realization that America is more than a location to me; it is my home. There I am part of a tribe and a clan that never use the words “tribe” and “clan” to identify ourselves. Like Ghana, the United States is a nation of many peoples who are trying to be one country. Ghana has been far more successful at forging a true national identity. Most of her neighbors on the African continent are torn by ethnic and religious strife. I pray for Ghana. I pray for America. I pray for our world.

Link

to photo journal

https://www.flickr.com/gp/150132485@N03/Gx42t6

Video

interview

https://youtu.be/GpB-8mdQ6EE

[1] Stacey Tisdale et al., “What The Candidates Need To Know About Blacks And Money,” HuffPost, 43:53 500, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/what-the-candidates-and-m_b_12365848. According to this study, African Americans have over $1.2 trillion in buying power. The author argues, “if black wealth were a country, it would be the 15th richest nation on the planet.”However, one should not forget that Black wealth in America is only a fraction of White wealth.

Excellent essay- thanks for sharing your journey!

Shalom Rabbi Sholomo! Magnificent piece my lord! I ran across it after hearing Dr. Henrik Clarke speaking in a lecture about Black Jews who had lived in Ghana for four hundred years; when I searched for a book related to that topic, your article was front and center! Shalom Aleichem Rav!